1. Introduction to GNU Radio and Signals

This page shall guide you through our primary tool – GNU Radio. GNU Radio is very popular and robust Software defined radio package. It is open source and is relatively very easy to use. All “coding” is done using flowgraphs comprised of interconnected Digital Signal Processing (DSP) blocks. Most commonly used blocks come predefined as part of the software package however one can program their own blocks as well.

- 1. Introduction to GNU Radio and Signals

1.1. Installing GNURadio

1.2. GQRX - It’s cool

GQRX is an application written using gnuradio. It acquired data from the dongle and has a set of preset options to manipulate said signals. It can even store raw data for custom decoding. Install gqrx

First, we make sure our dongle is plugged into the USB see if it is detected by the computer by typing airspy_info. If we installed all software correctly it should return information about the dongle and no errors. If everything is in order the type in terminal:

gqrx

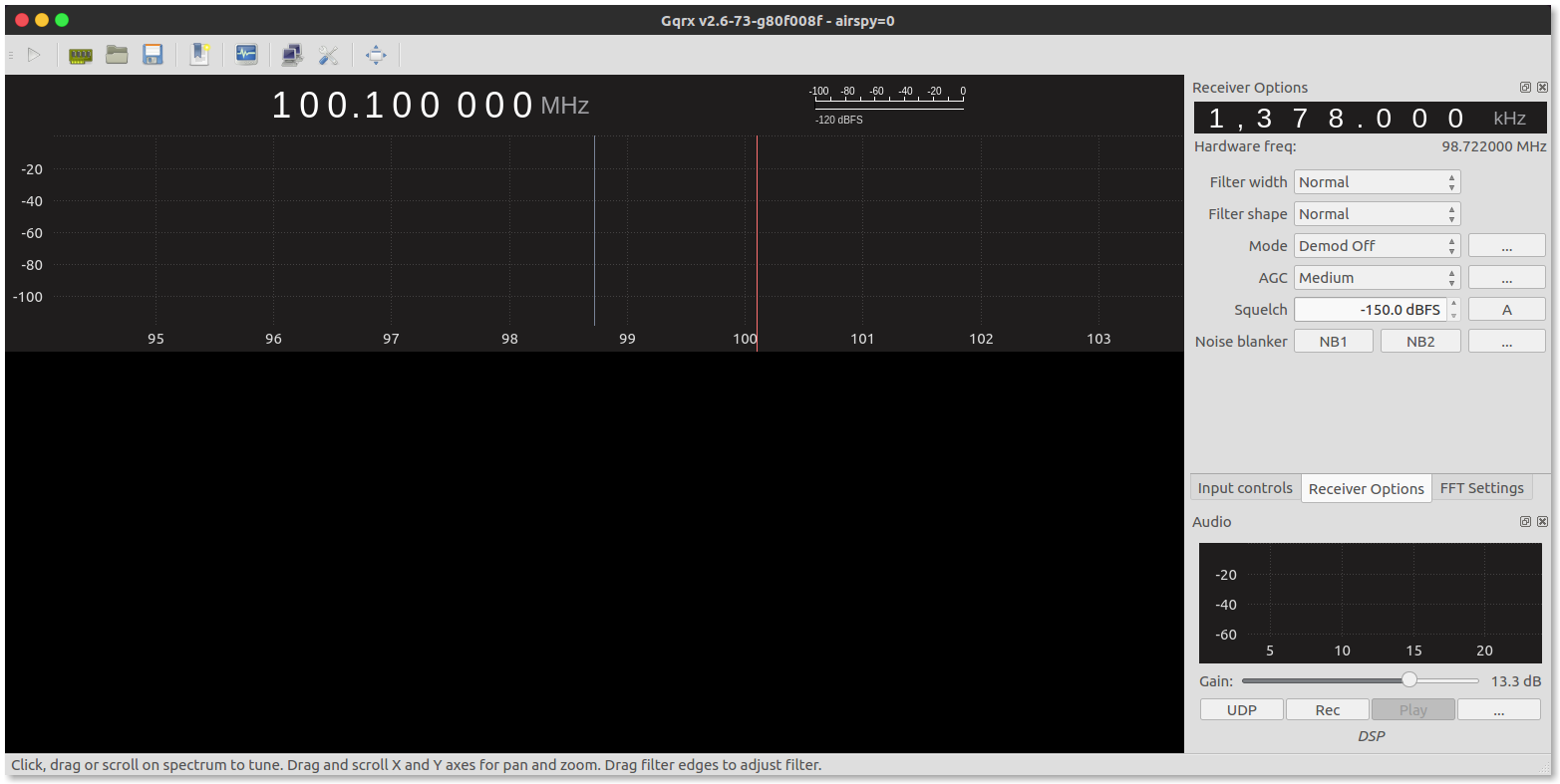

It will open a window that looks like this.

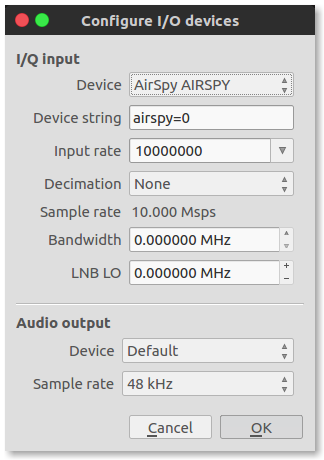

If you are using for the first time the hardware setting window/(IO setting) should open automatically and also automatically detect the dongle. If not chose AirSpy AIRSPY from the drop down.

Otherwise you can open it by clicking on the “circuit board” icon next to the play triangle. The I/O device settings should look like this:

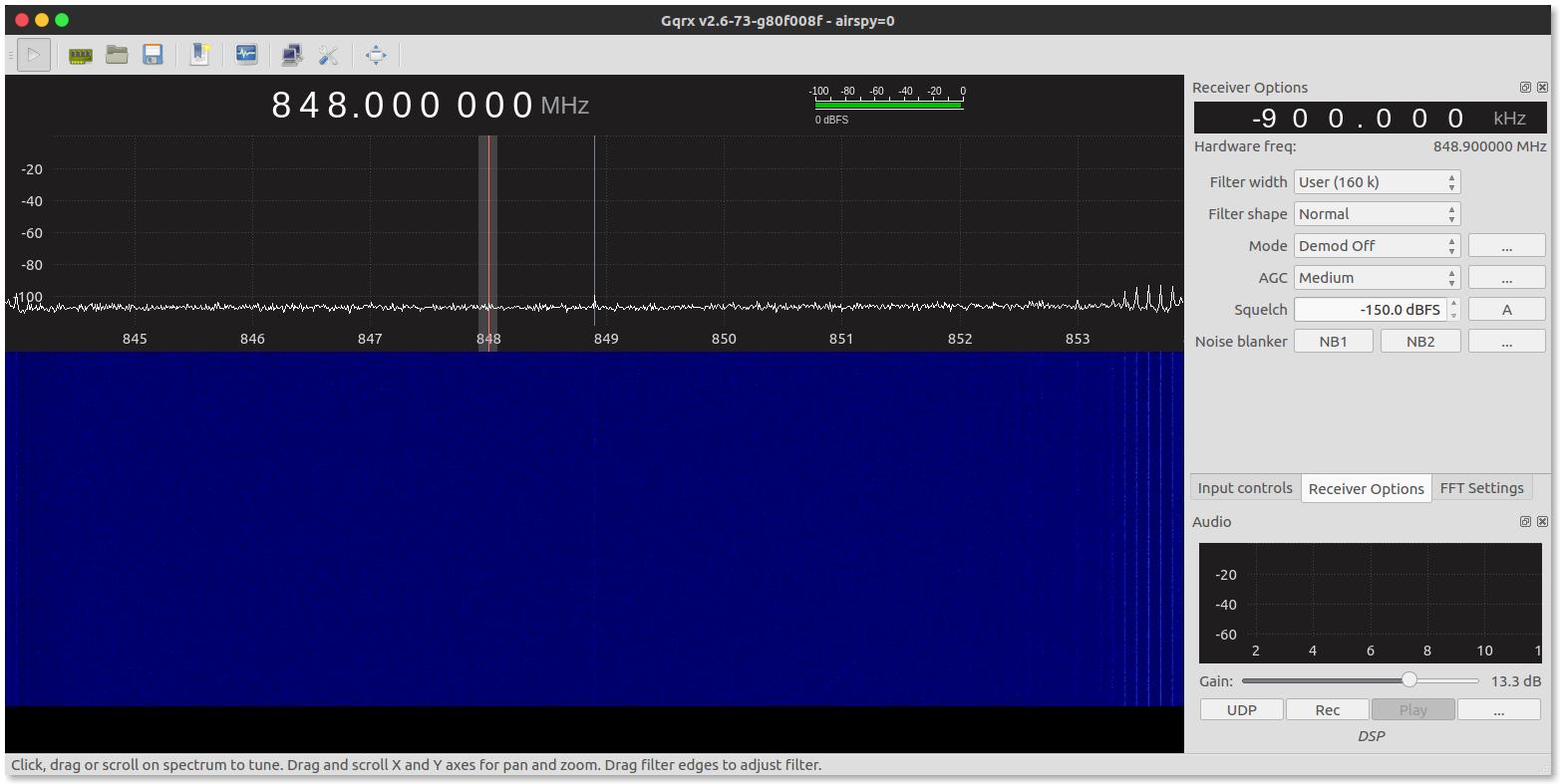

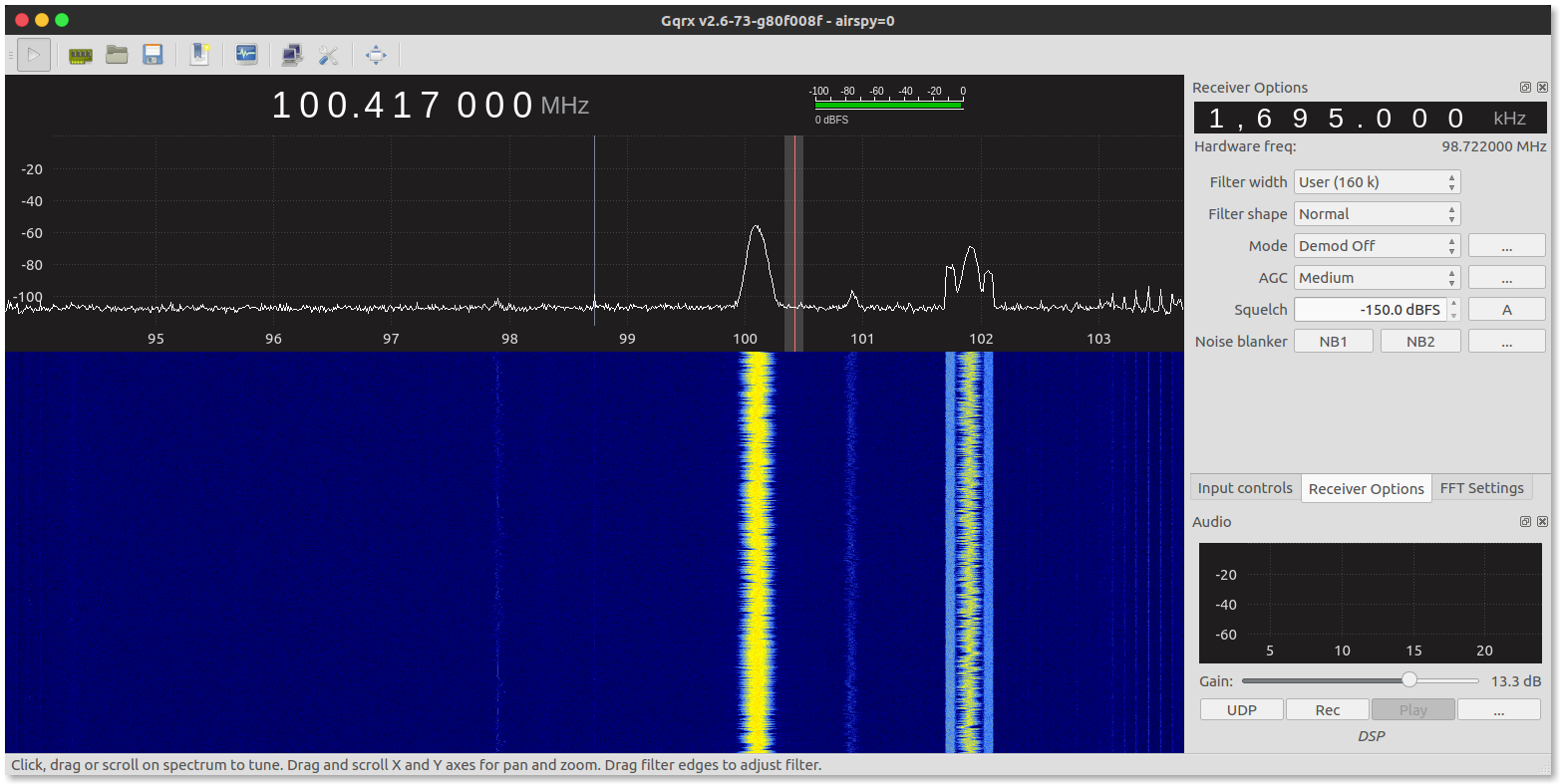

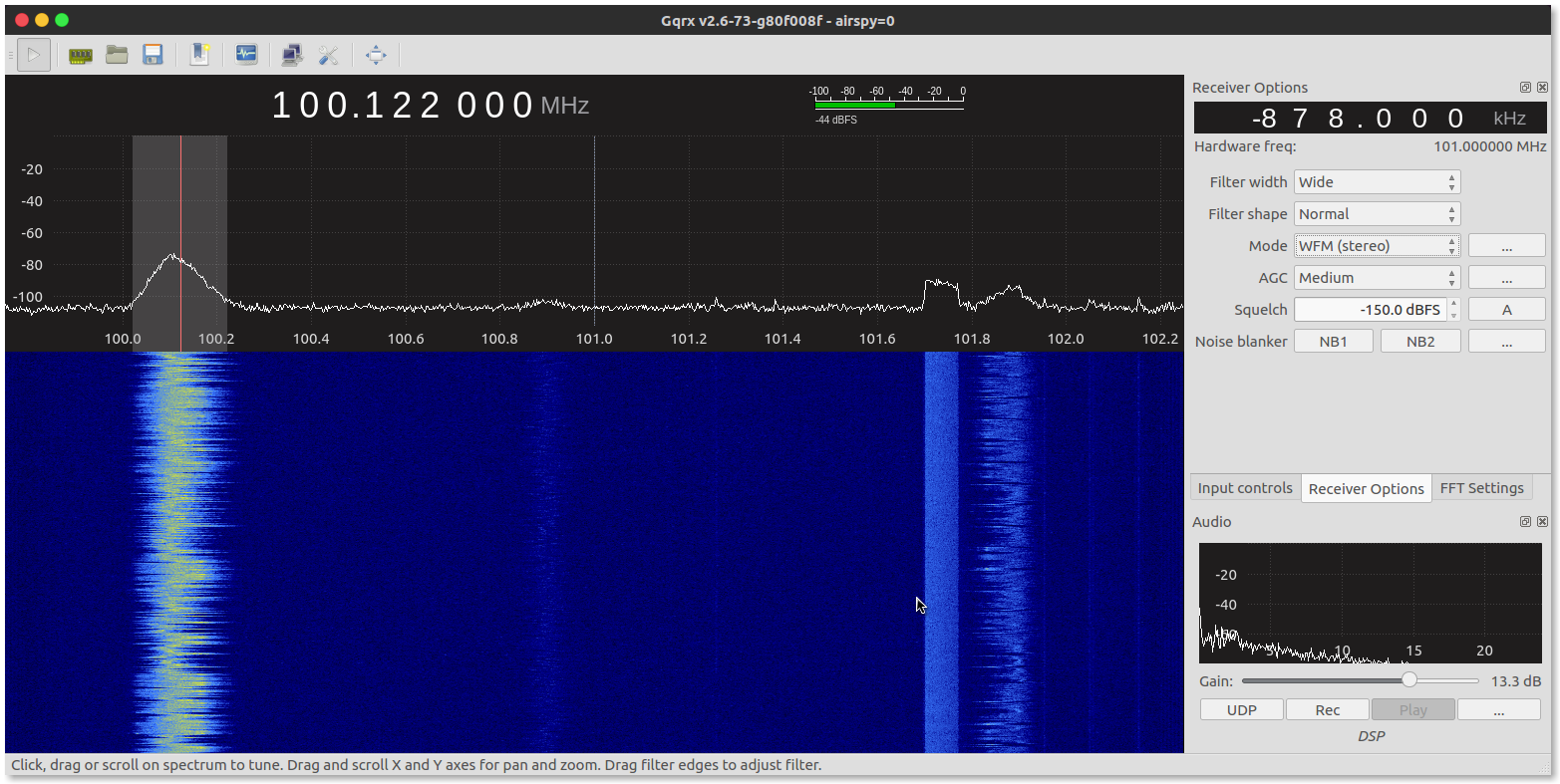

Once it is all in order click play. The window should show the spectrum as such:

Hit play. Change the frequency to 100 Mhz. Notice the bright bands on the waterfall and the peaks, these are local FM stations

Since the sample rate is very high (a feature of this particular hardware). We click on the “circuit board” button again and change input rate 2500000 (from the drop down). In the receiver options the right change Mode to WFM ( wideband FM ) from the drop down and et voila old timey over-the-air radio on your space-age computer.

We can use this application to receive even decode to all kinds of signals from 24 – 1800 Mhz. Check out Section 1.4

1.2.1. Getting Started with GNU Radio

As mentioned earlier, gqrx has GNUradio as its engine. We can start developing using this tool right away by typing gnuradio-companion in the terminal:

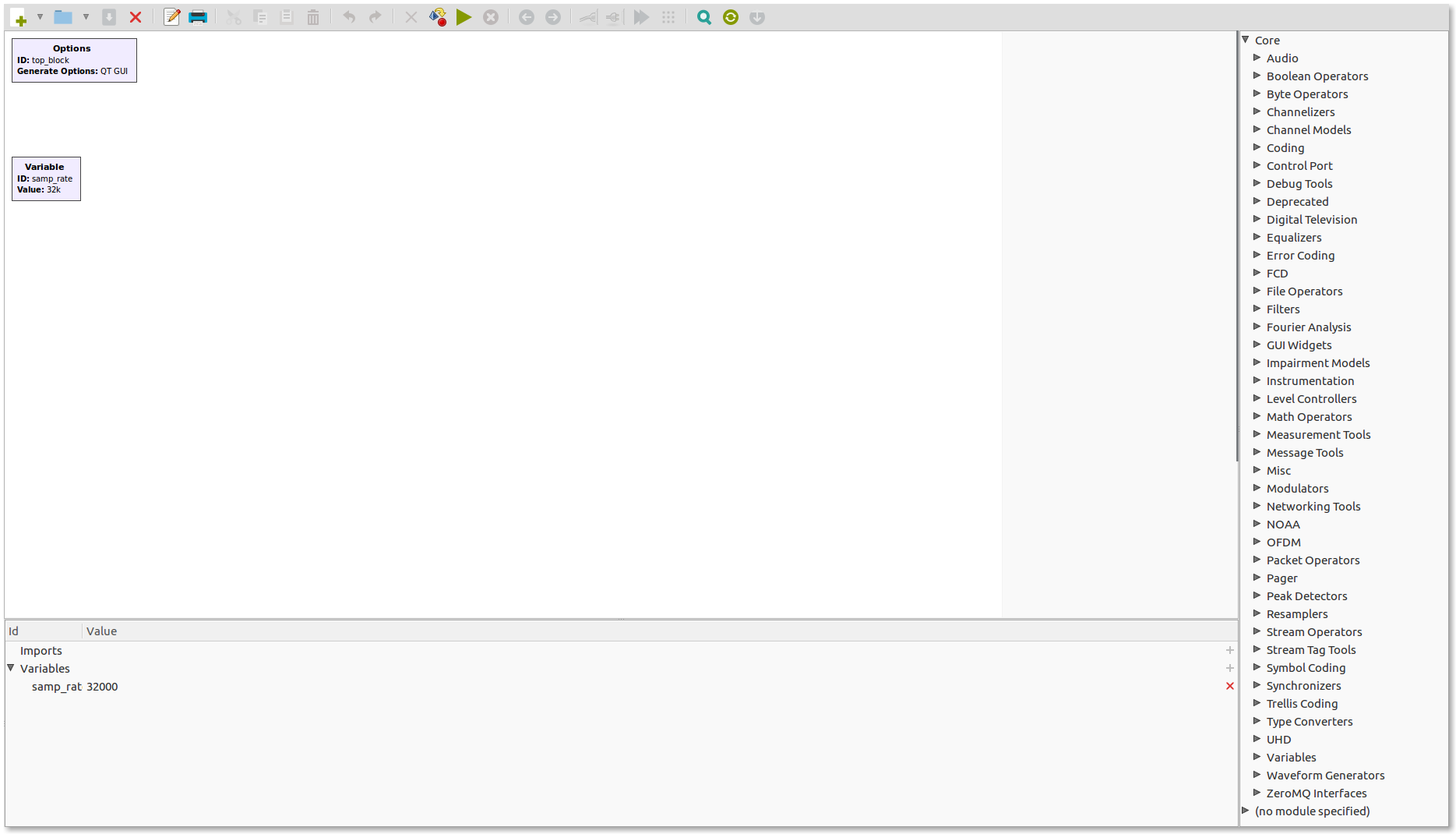

This opens GNU Radio Companion (GRC):

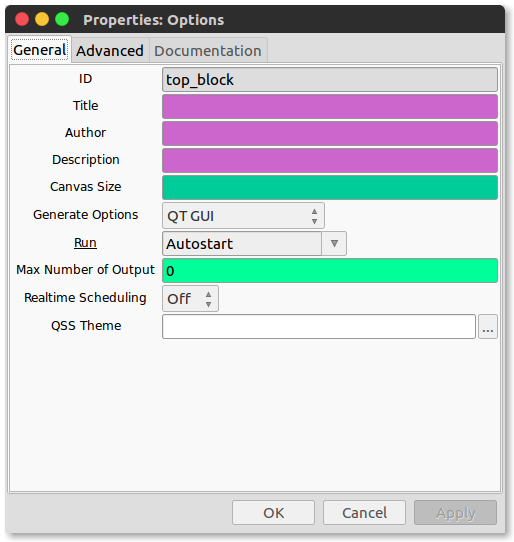

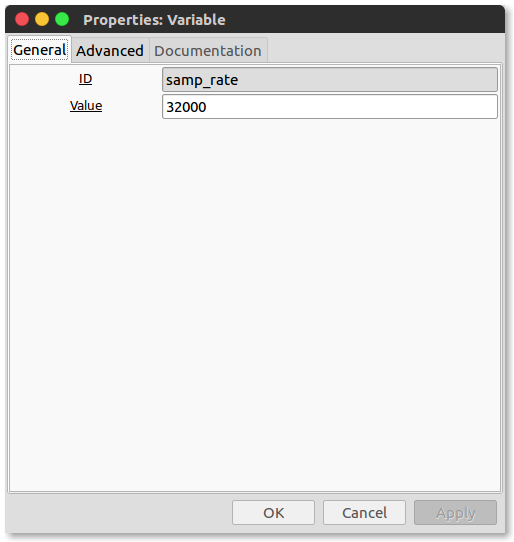

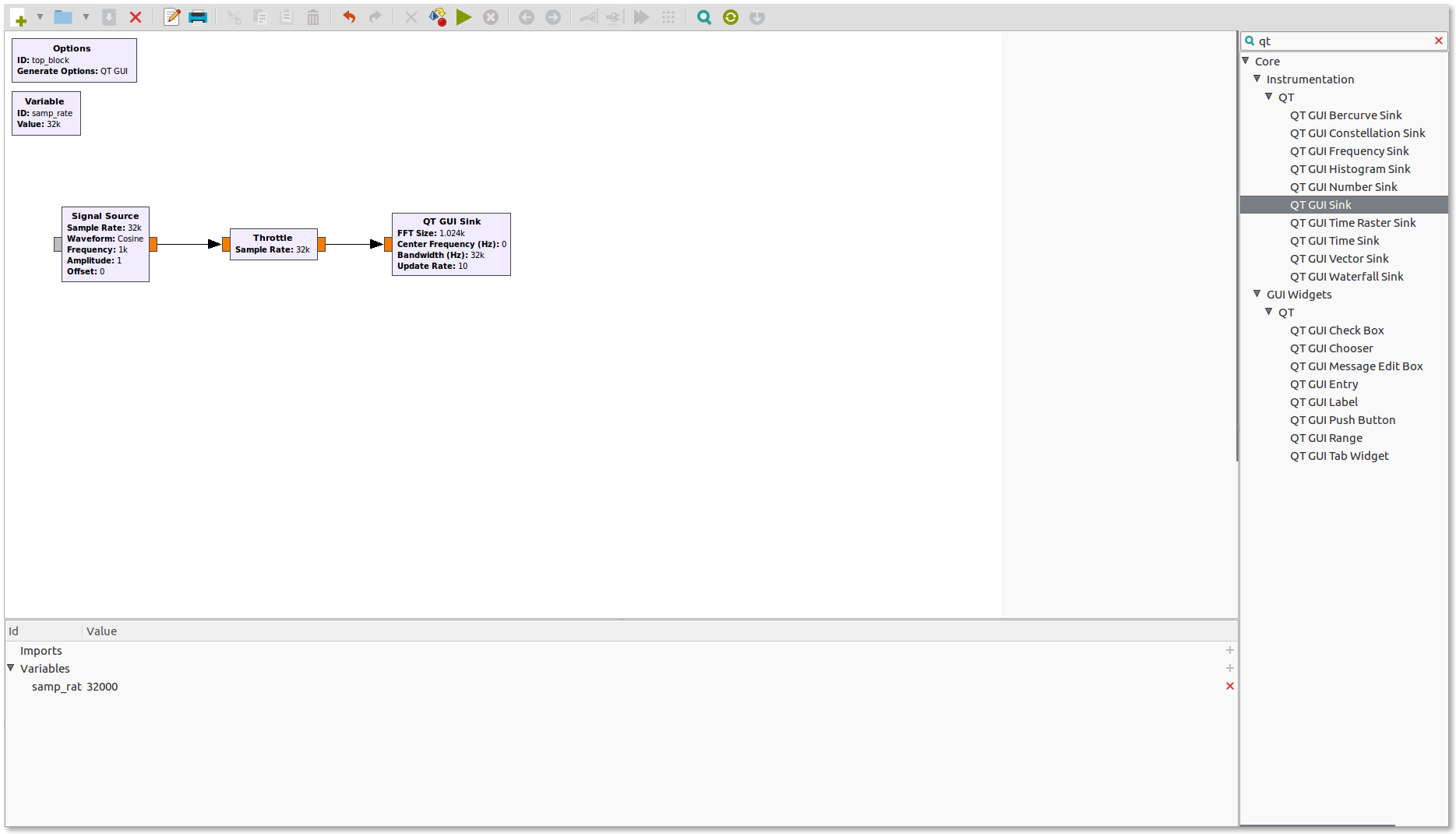

The “Options” block at the top left is used to set some general parameters of the flowgraph, such as metadata of the flowgraph like the title, author, etc., the graphical user interface (GUI) for widgets and result displays, or the size of the canvas on which the DSP blocks are placed. Right-click on the block and click on Properties (or double-click on the block) to see all the parameters that can be set. Below the Options block is a “Variable” block that is used to set values to variables that are used throughout the flowgraph like the sample rate, e.g.,\(F_s = 32000 Hz\)

Every GRC window has these two very basic blocks. The white space is called the GRC canvas.

1.3. Let’s get Familiar

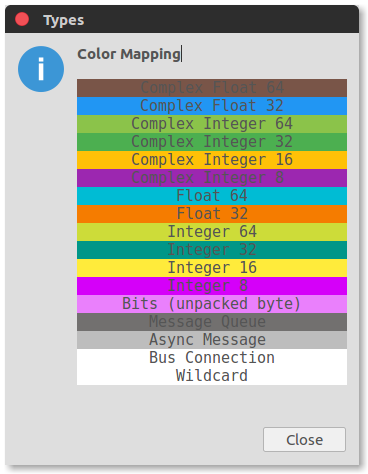

On the right side of the window is a list of the block categories that are available. Click on a triangle next to a category to see what blocks are available in that category. We will look for the waveform generator category to look for the signal source block. Alternatively, we can click on the magnifying/looking glass to the top right and search for the block we need. We will add the signal source block to the canvas by double clicking on signal source

To move a block on the canvas, grab it with the cursor, press the left mouse button, and move the block to the desired location. You can also rotate blocks by right-clicking on them and then clicking either “Rotate Counterclockwise” or “Rotate Clockwise”. Blocks can also be temporarily disabled by clicking on “Disable”, which is useful for debugging and what-if questions. The rearranged blocks with the options for the “Signal Source” visible are shown next.

Aside

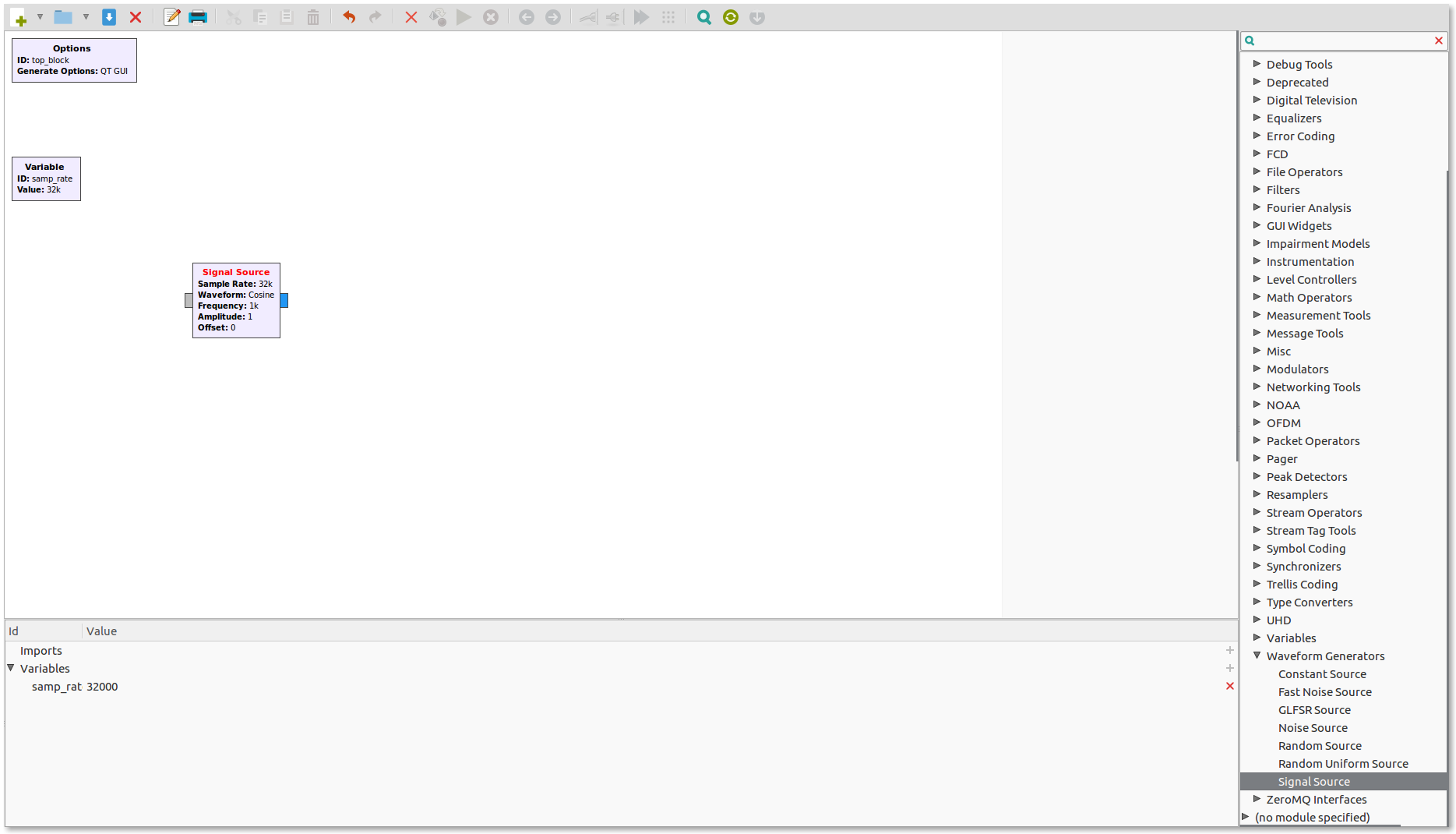

We notice that the “Signal Source” block has two ports, a grey one on the left and a blue one on the right. The color of a port indicates the type of data generated for an output port or the type of data accepted for an input. The most common data types that we will use are:

- Blue for complex-valued 32-bit floating point data samples (32 bits for each, real and imaginary part).

- Orange for real-valued 32-bit floating point data samples

- Blue-Green for real-valued 32-bit (long) integer data samples

- Yellow for real-valued 16-bit (short) integer data samples

- Magenta for real-valued 8-bit (byte) integer data samples

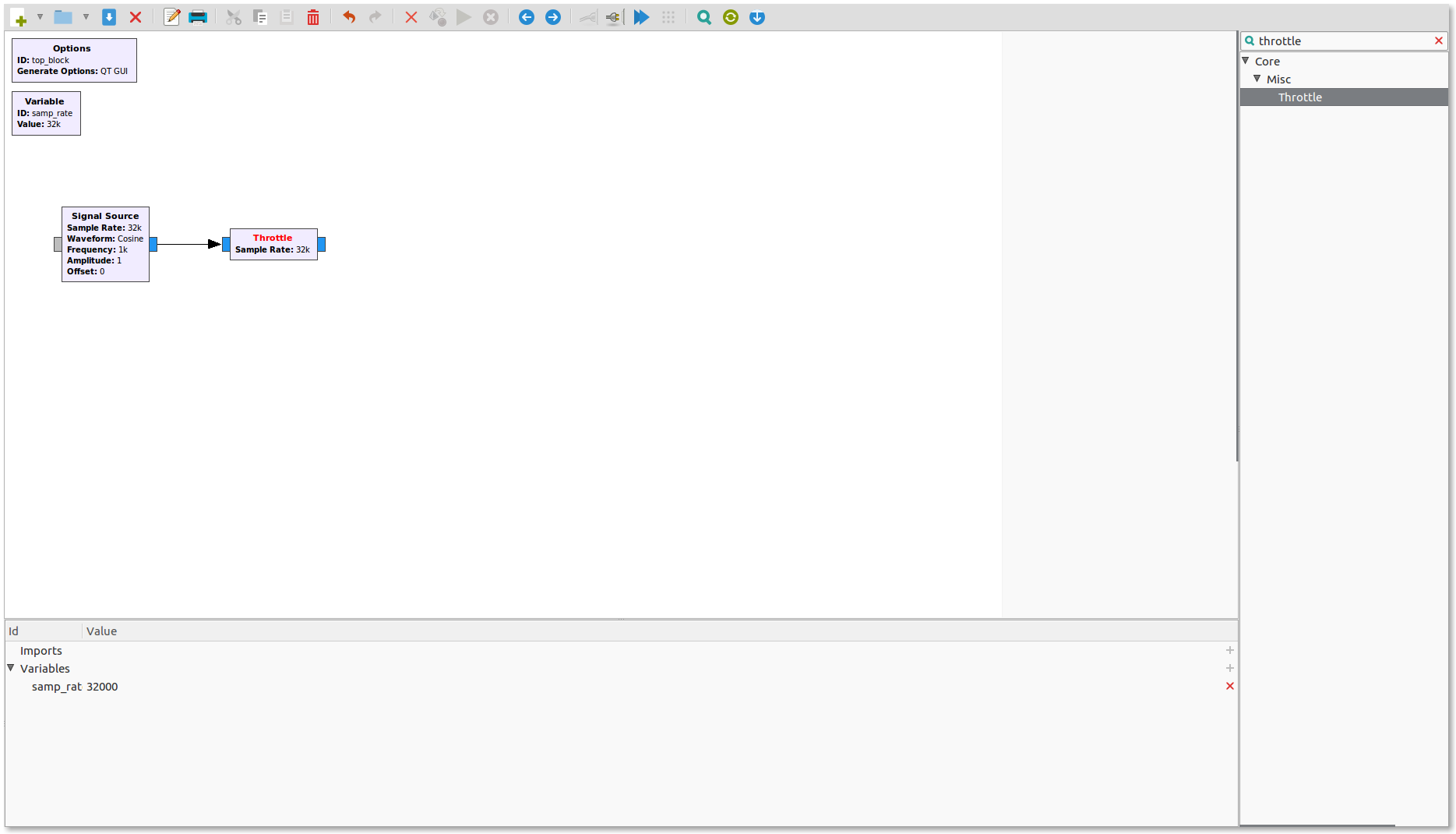

GNU Radio uses a stream processing model to process large amounts of data in real-time as opposed to a array processing environment (like Matlab). In practice this means that each signal processing block has an independent scheduler running in its own execution thread and each block runs as fast as the CPU, dataflow, and buffer space allows. If there is a hardware source and/or sink that imposes a fixed rate (e.g., 44100 samples/sec for an audio signal, or 10 Msamples/sec for an SDR interface), then that determines the overall processing rate. But if both the source and the sink are implemented purely in software (like a signal generator feeding a time or frequency display), then some form of timing constraint must be imposed in software to limit the processing speed to a specified sampling rate. A special “Throttle” block that we will frequently encounter is used for this purpose. The figure below shows a “Throttle” block connected to the output of the “Signal Source” that we placed earlier. Click on one port follow it by clicking on the other port: this wires the output port of one block to the input port of another block. For the flowgraph to work both ports must use data of the same type (i.e., both ports must be of the same color). If they are of different types, then the arrow of the connection will be red instead of black. It is worth noticing that the word “Throttle” appears in red on the Throttle block, indicating that there is something wrong with this block in the flowgraph. Things that can go wrong are unspecified or undefined parameters or, as is the case above, connections to/from some ports are missing. If you see any red arrows or red writing in a flowgraph you will not be able to run the flowgraph until the offending condition has been fixed.

1.3.1. A Cosine Waveform generator

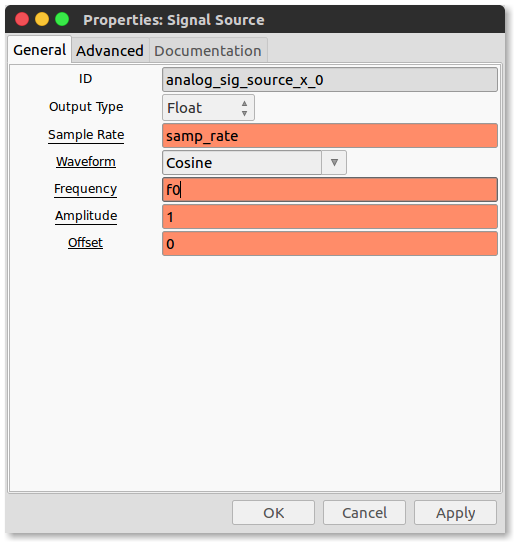

For our first experiment we want to generate a real-valued cosine signal with frequency 1000 Hz (default for the “Signal Source”) and display it in the time and frequency domains. We start from a flowgraph which consists of a “Signal Source” connected to a “Throttle”. To make the output of the Signal Source real-valued, double-click on the block and in the Properties window that shows up click on “Complex” under “Output Type” and select “Float” as shown below. Then choose “QT” under “Instrumentation” (or just simply search for “QT GUI Sink”) and double-click on “QT GUI Sink”. This block will allow you to see the waveform at the input in the frequency as well as in the time domain. Change the data “Type” from “Complex” to “Float” and connect the input to the output of the “Throttle” block. Save the flowgraph, e.g., as ex01_1.grc

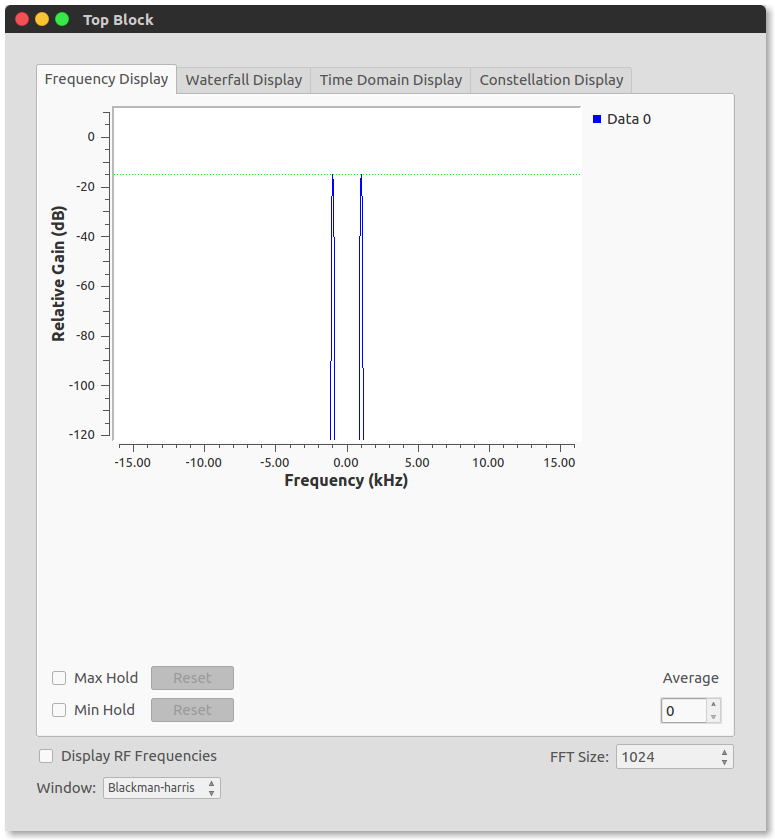

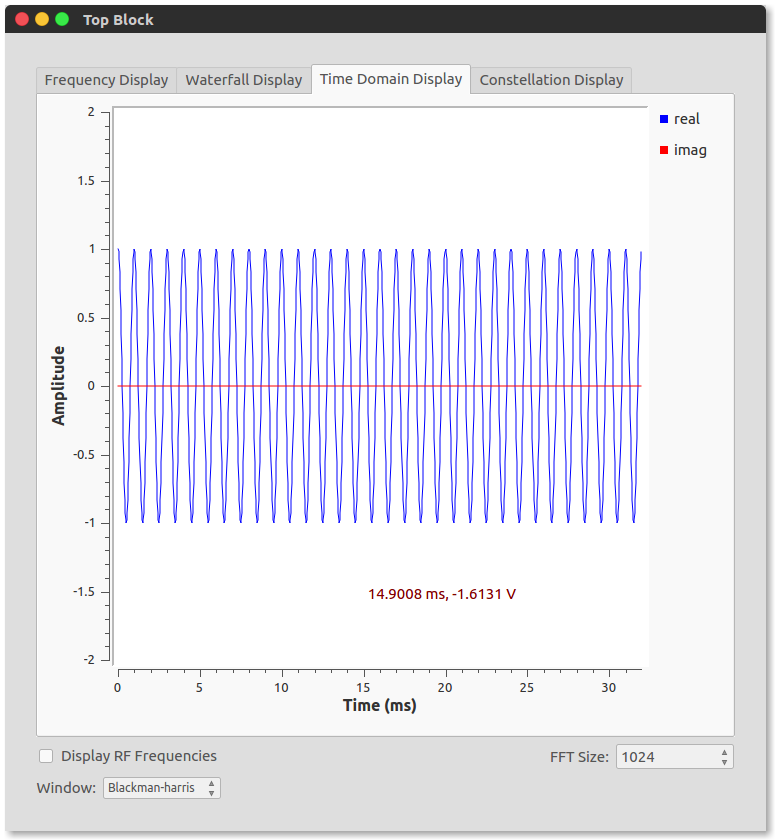

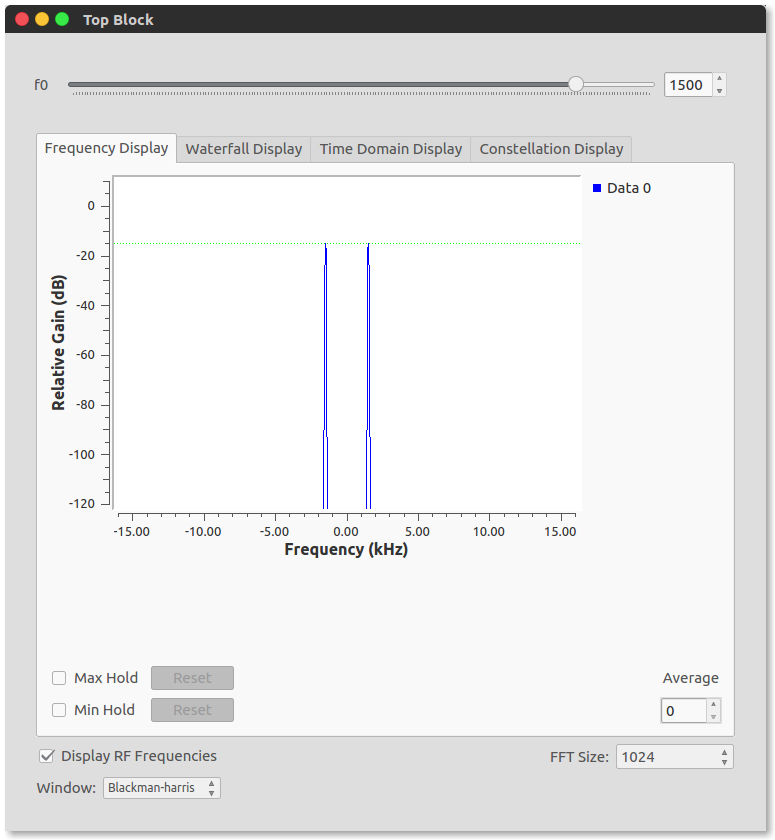

Now you can run the flowgraph by clicking on the green triangle above the canvas or by clicking “Run” on the menu bar. You can choose between the “Frequency Display” and the “Time Domain Display” tabs as shown below. Use the cursor to zoom in on a rectangular region, increase the FFT size to 4096 or 8192, choose different types of windows, e.g. “rectangular” or “Kaiser” and observe the effects, especially on the Frequency Display. Note that the Frequency Display shows power spectral density (PSD) which is essentially proportional to the magnitude squared of the Fourier transform.

1.3.2. A Cosine Waveform Generator with Variable Frequency and Sound

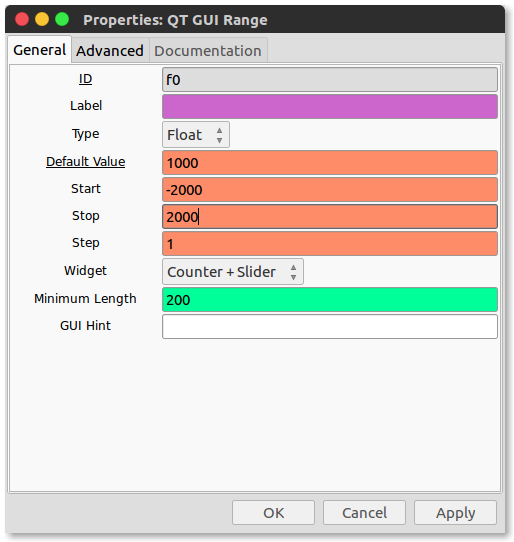

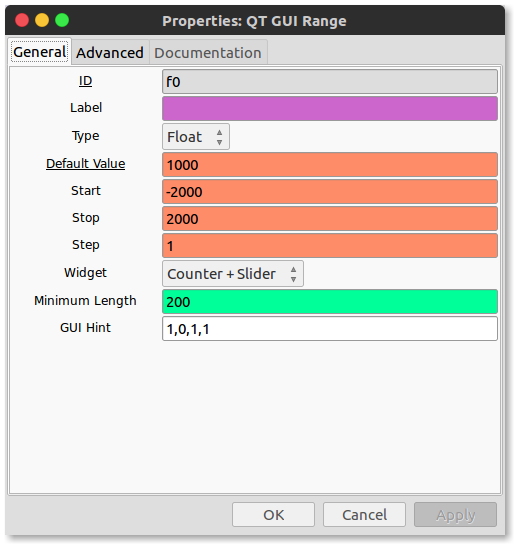

We can start from the ex01_1.grc flowgraph from our first exercise. Under “GUI Widgets” and “QT” select “QT GUI Range”. Double- click on the block so that you get to see its Properties. Change the “ID” from variable_qtgui_range_0 to f0. For the “Default Value” enter 1000. For the “Start” and the “Stop” values enter -2000 and 2000, respectively. Next we double-click on the “Signal Source” block and change the “Frequency” entry from 1000 to f0. The respective windows look like below:

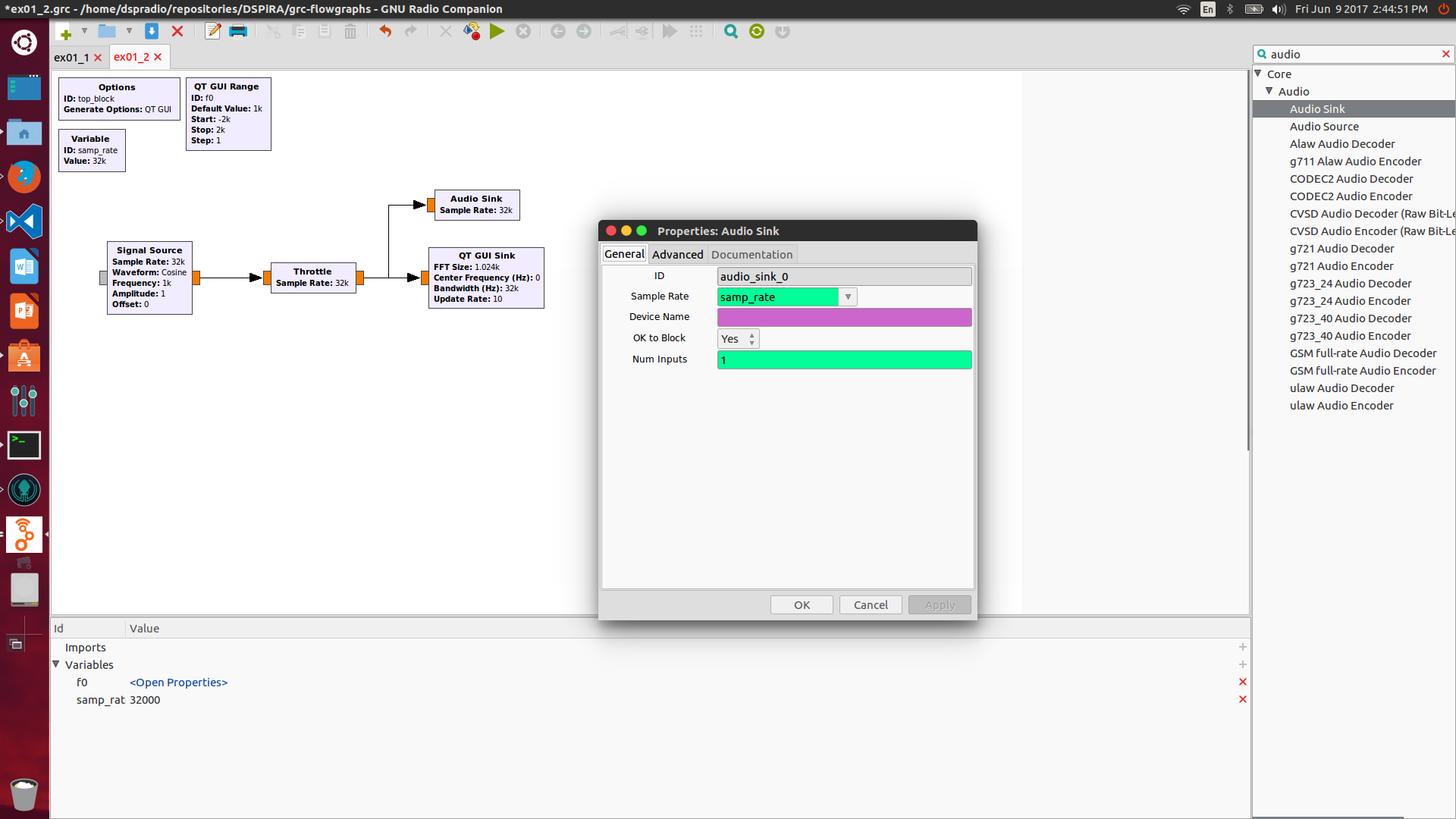

To add a sound output, select “Audio” and then double-click on “Audio Sink”. Connect the “Audio Sink” input to the “Throttle” output and leave the “Sample Rate” at the default value of samp_rate (32000 samples/sec).

Save the flowgraph, e.g., as ex01_2.grc. If you run the flowgraph now you will get a slider for changing the “Signal Source” frequency from -2000 to +2000 Hz, you will hear the corresponding sound, and you can choose to display the “Frequency” or the “Time Domain” graph.

Difference between \(+ve\ \&\ -ve\) frequencies?

1.3.3. A General Waveform Generator

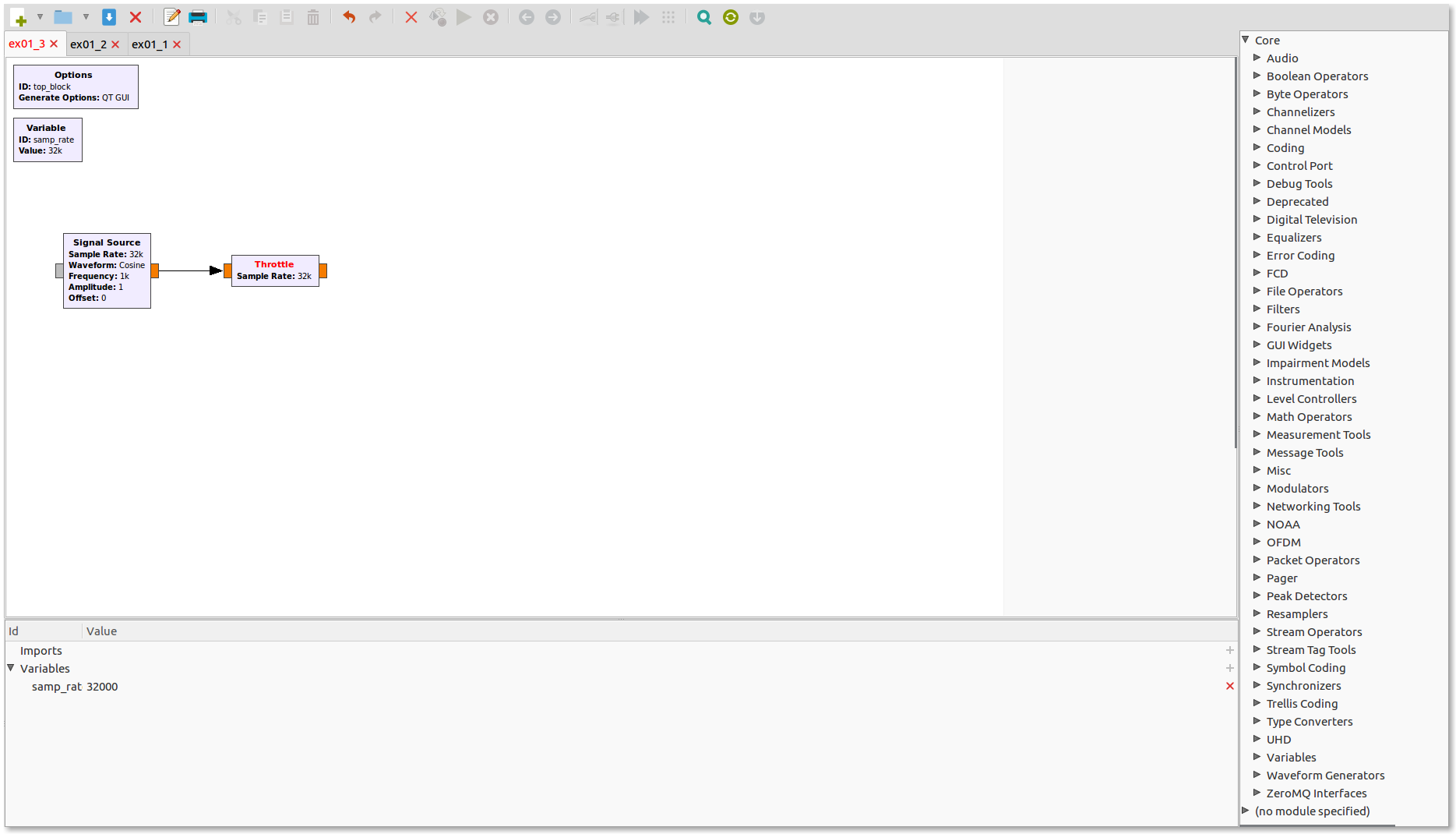

In this subsection we shall expand upon the previous exercise and learn how to play around with various useful GNU Radio Companion features. Let us begin by changing ex01_2.grc flowgraph by removing the “Audio Sink” and the “QT GUI Sink”. Save this new flowgraph as ex01_3.grc

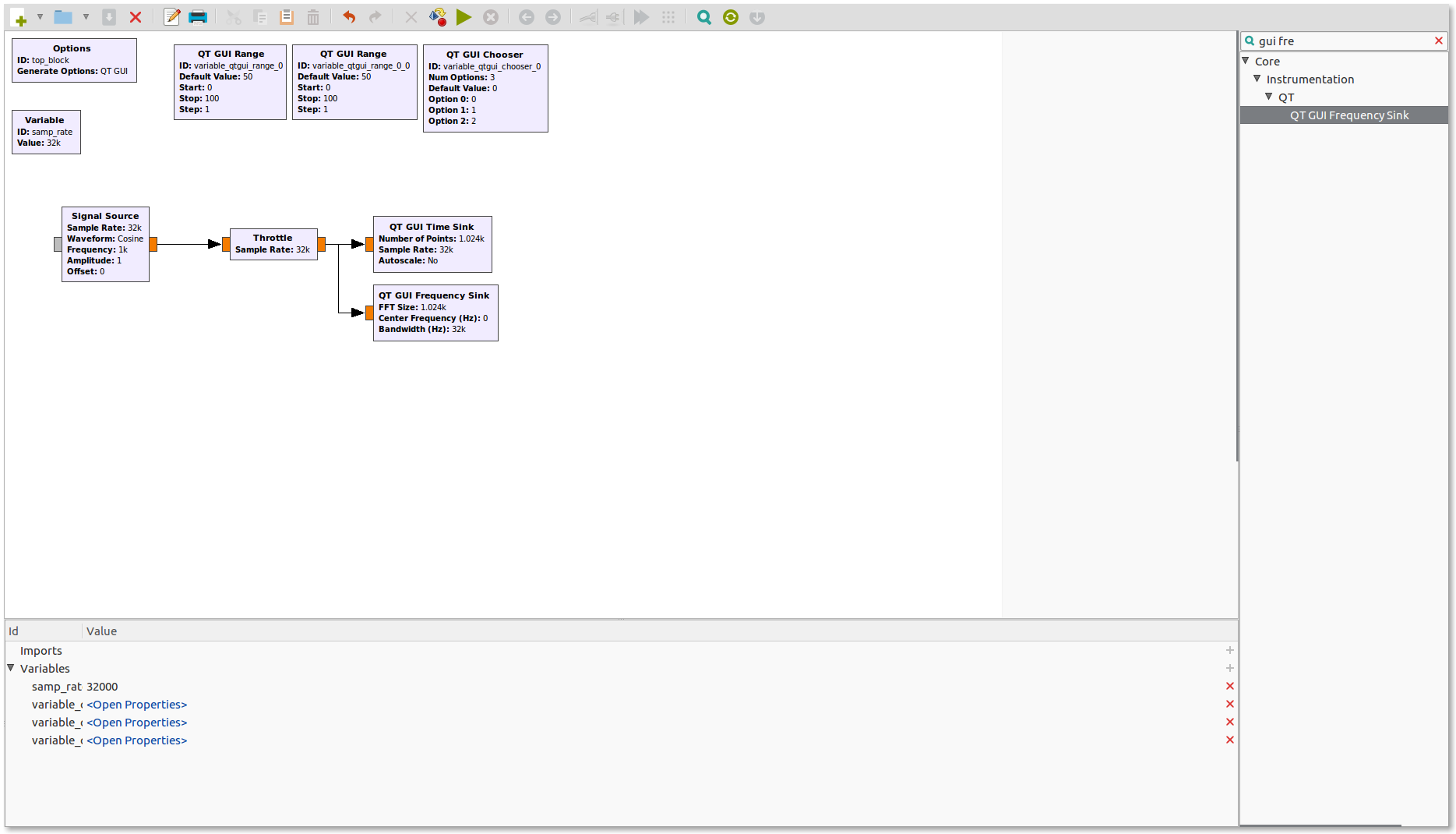

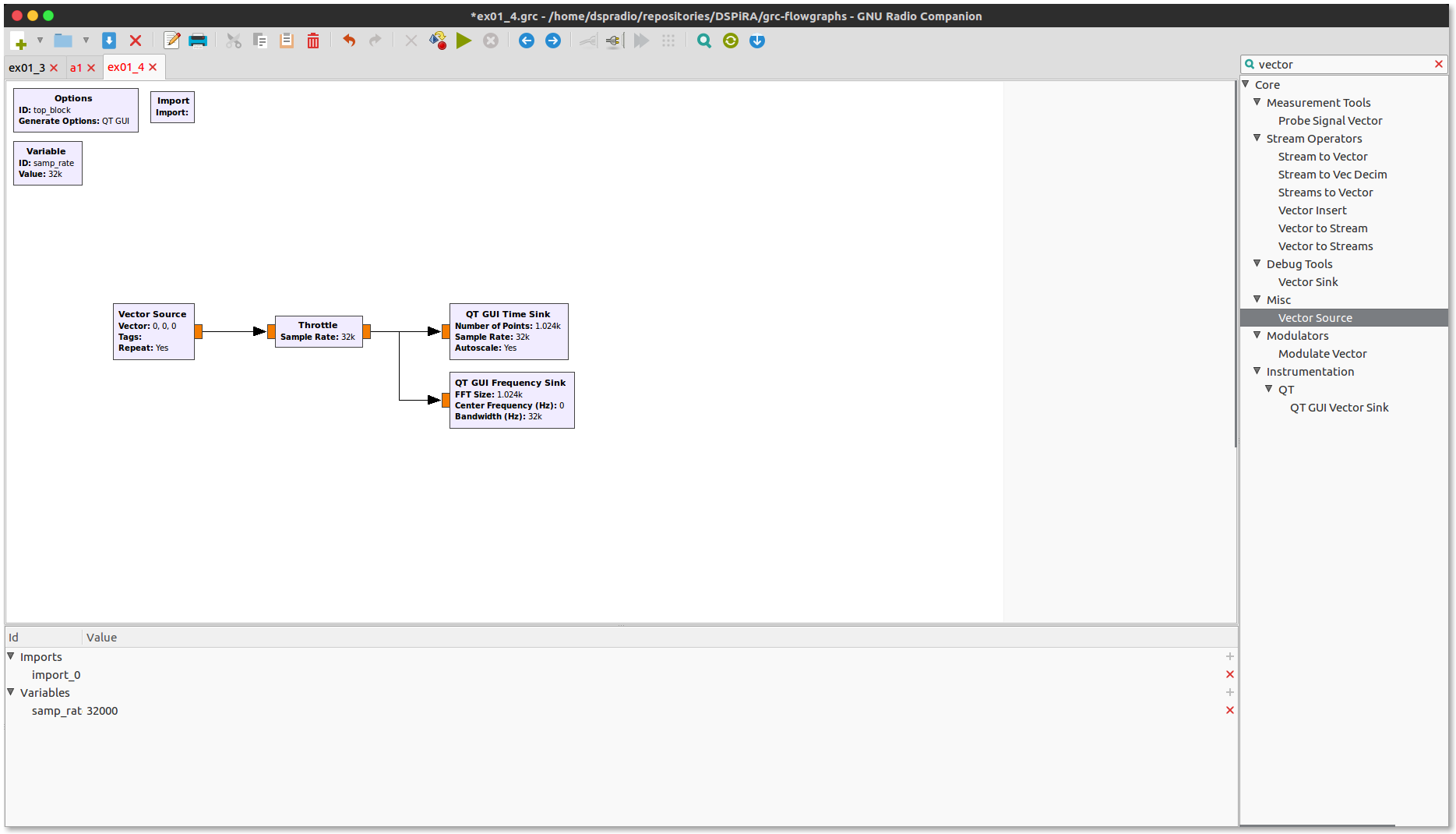

We would like to build a waveform generator that can produce real-valued “Cosine”, “Rectangular”, and “Triangular” waveforms with variable frequency and variable dc offset. To this end we need “QT GUI Range” blocks and a “QT GUI Chooser (from “GUI Widgets” and “QT”). Connect a “QT GUI Time Sink” and a “QT GUI Frequency Sink” (from “Instrumentation” and “QT”) to the output of the “Throttle” Block. Change the input type of the Sink blocks from “Complex” to “Float”. The flowgraph should look like this:

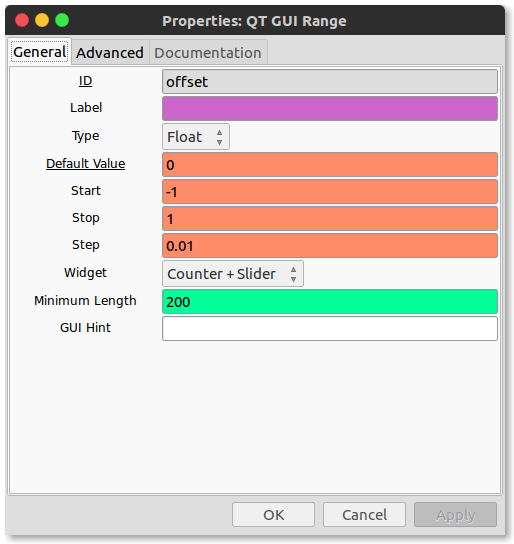

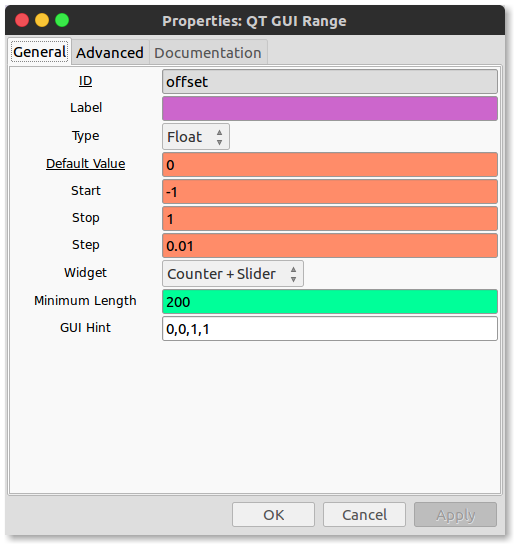

Now, double-click on the second “QT GUI Range” which will be used to adjust the offset of the waveform and modify the “Properties” as shown below:

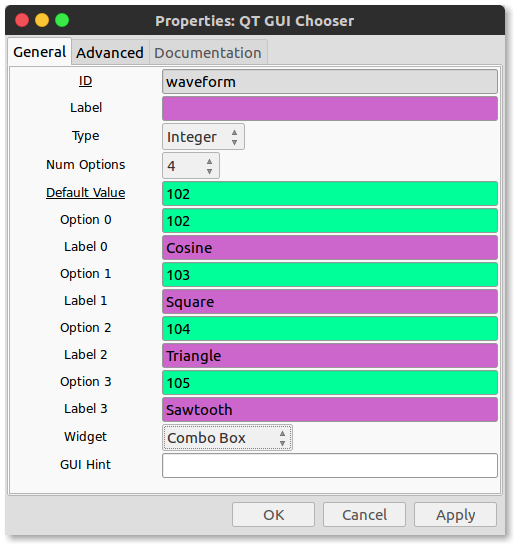

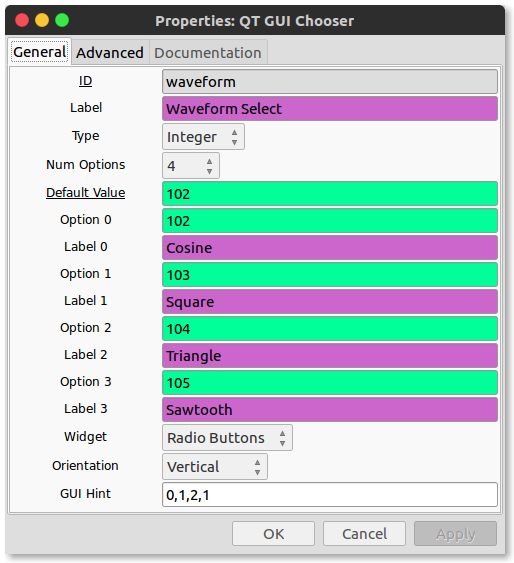

Next, double-click on the “QT GUI Chooser” that will be used to select different waveforms. The (integer) code for “Cosine” is 102, for “Square” it is 103, for “Triangle” it is 104 and for “Sawtooth” it is 105

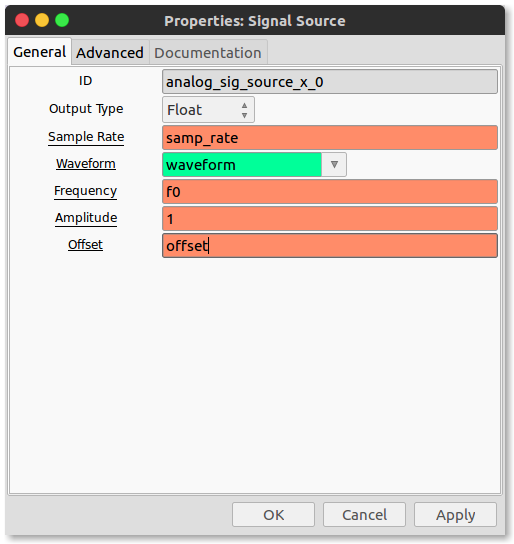

Finally, double-click on the “Signal Source” block and modify the “Properties” to look as follows.

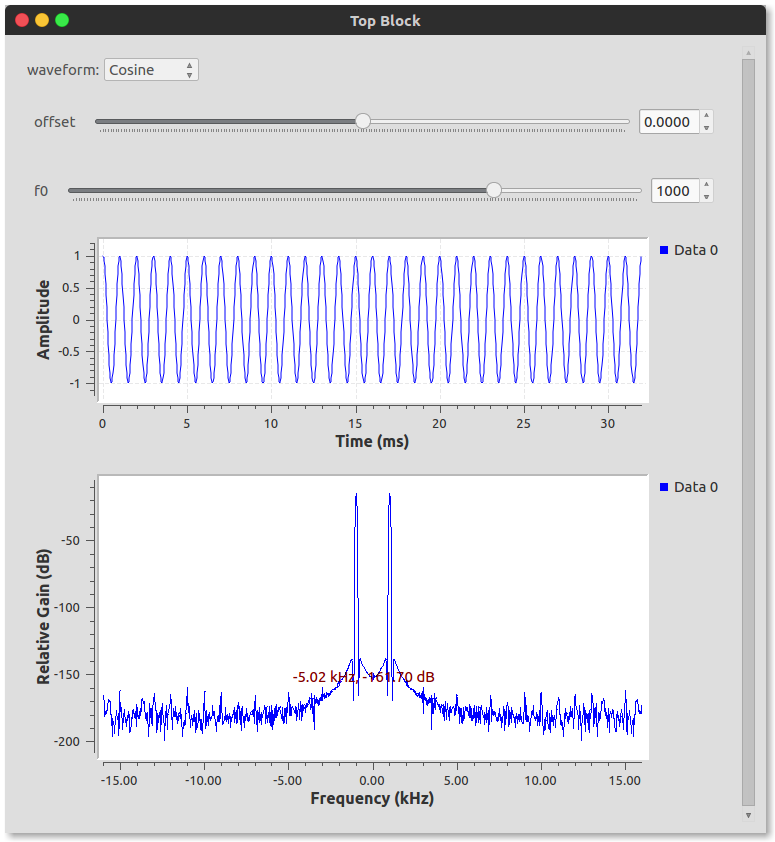

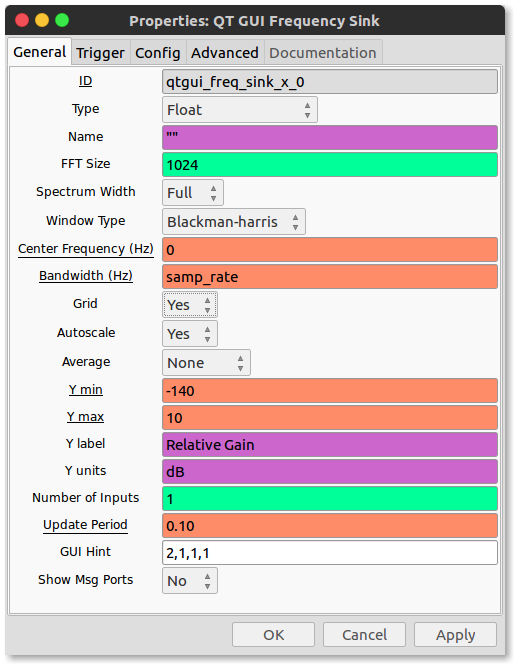

Double click on the sinks and change to autoscale property to “Yes” respectively. Click the green triangle above the flowgraph or click on “Run” and “Execute” in the GRC menu bar. The output is as below:

The arrangement of graphical elements, such as sliders, choosers, time and frequency sinks, etc., used in a GRC flowgraph can be modified by specifying grid positioning arguments in the “GUI Hint” fields of individual blocks. A grid positioning argument is a list of four integers of the form

row, column, row span, column span

If the “GUI Hint” entry is left blank, then the graphical elements are stacked vertically on top of each other. Otherwise, they are placed in the specified row and the specified column, spanning row span rows and col span columns. Note that rowspan >= 1 and colspan >= 1 are required.

| (0,0) | (0,1) | (0,2) | (0,3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1,0) | (1,1) | (1,2) | (1,3) |

| (2,0) | (2,1) | (2,2) | (2,3) |

We shall rearrange our signal generator with the following GUI Hints

| Offset Slider (0,0,1,1) | Waveform Selector (0,1,2,1) |

|---|---|

| Frequency Slider (1,0,1,1) | ” |

| Time Display (2,0,1,1) | Frequency Display (2,1,1,1) |

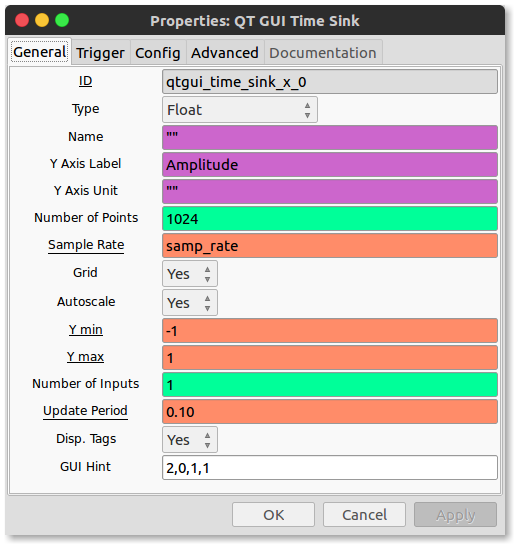

The GUI hints are updated as seen the following dialog boxes:

This give the following Output:

1.4. GNU Radio and Python

GNU Radio is written in python and the final code that does the magic is all in Python. Python is very powerful programing language known for its readability and versatility. The flow graphs created in GNU radio companion are converted into a Python script. All the predefined blocks are written in Python and/or C. One can make their own GNU Radio blocks by coding in Python or C. If you want to know how to do this in depth you can click on this guided tutorial here

1.4.1. Arbitrary Function generation

The fact that the end product and much of the guts of GNU Radio is in Python implied we can exploit the standard library of python or our own scripts to test out several things. We shall look into making any arbitrary wave form. This is useful for testing systems designed in gnuradio

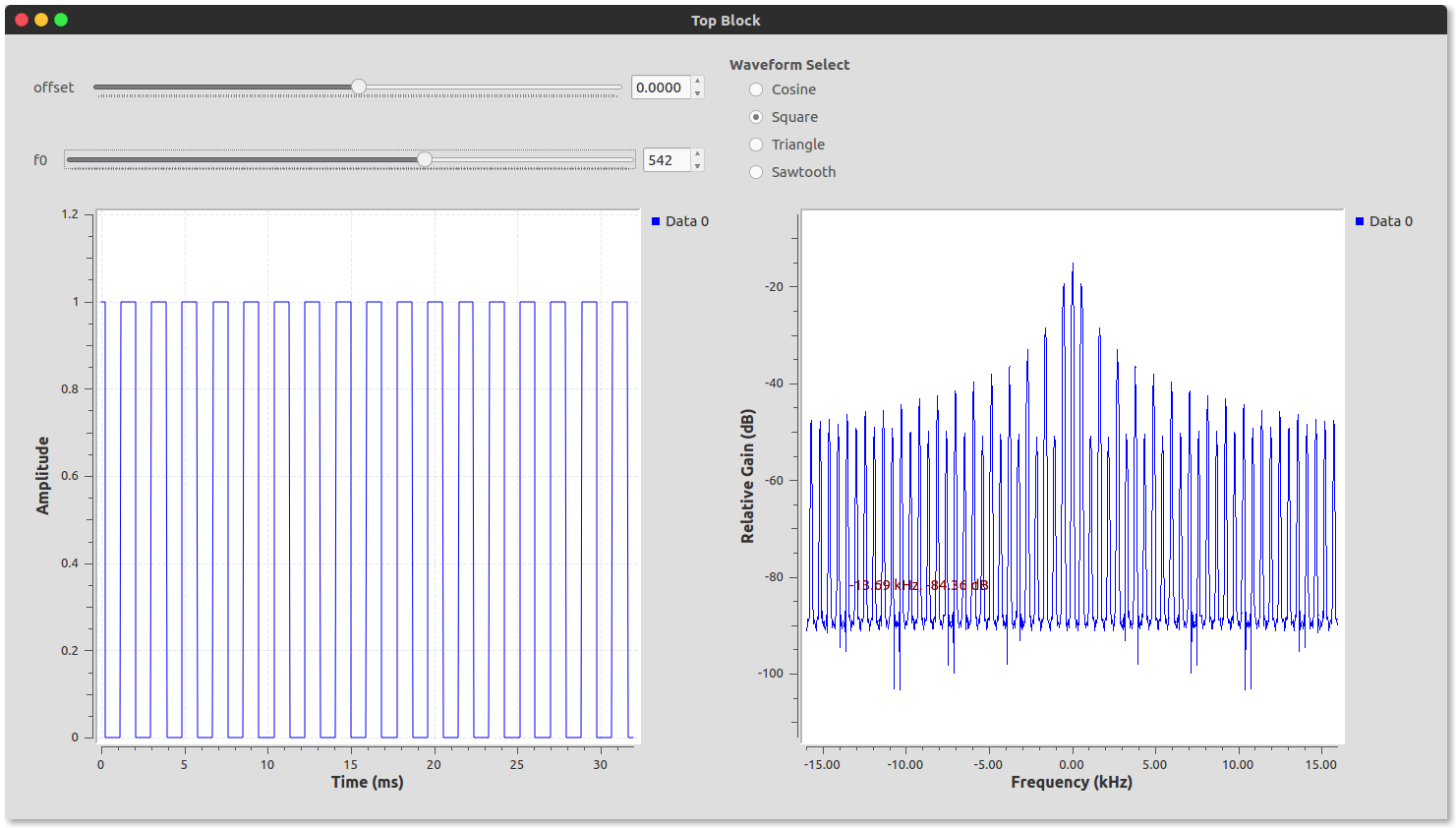

To import a library from python we use the “import” block and we shall employ the “vector source” block to input our arbitrary function. We shall construct a flow graph similar to ex01_3.grc except we remove the “signal source” and replace with “vector source”, add an “import block” and we shall not worry about the GUI elements for this one. We should have a flowgraph that looks like this:

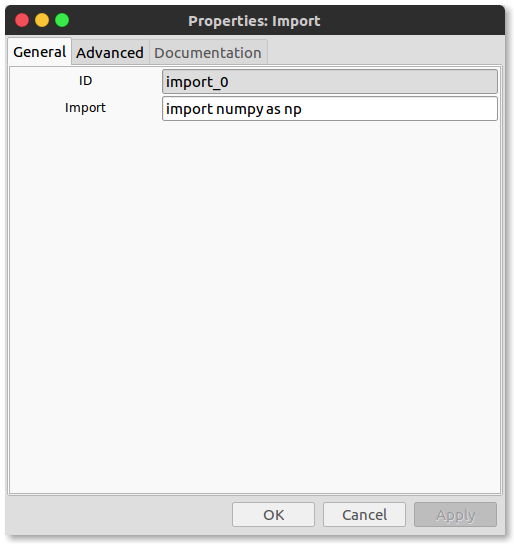

We shall import a standard library called numpy. It allows us to make matrices/vector and manipulate them easily. Double click the import block and fill out the import field as below:

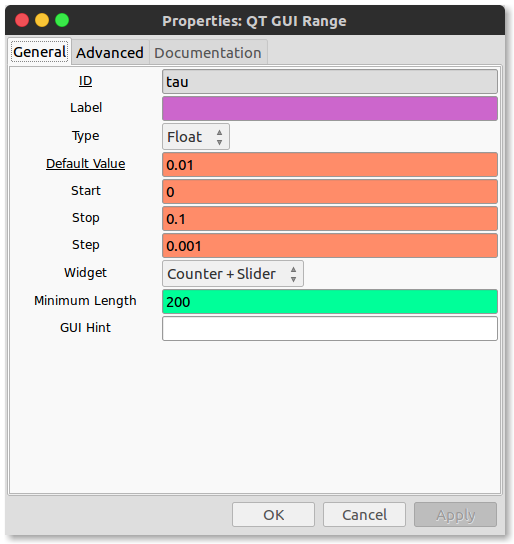

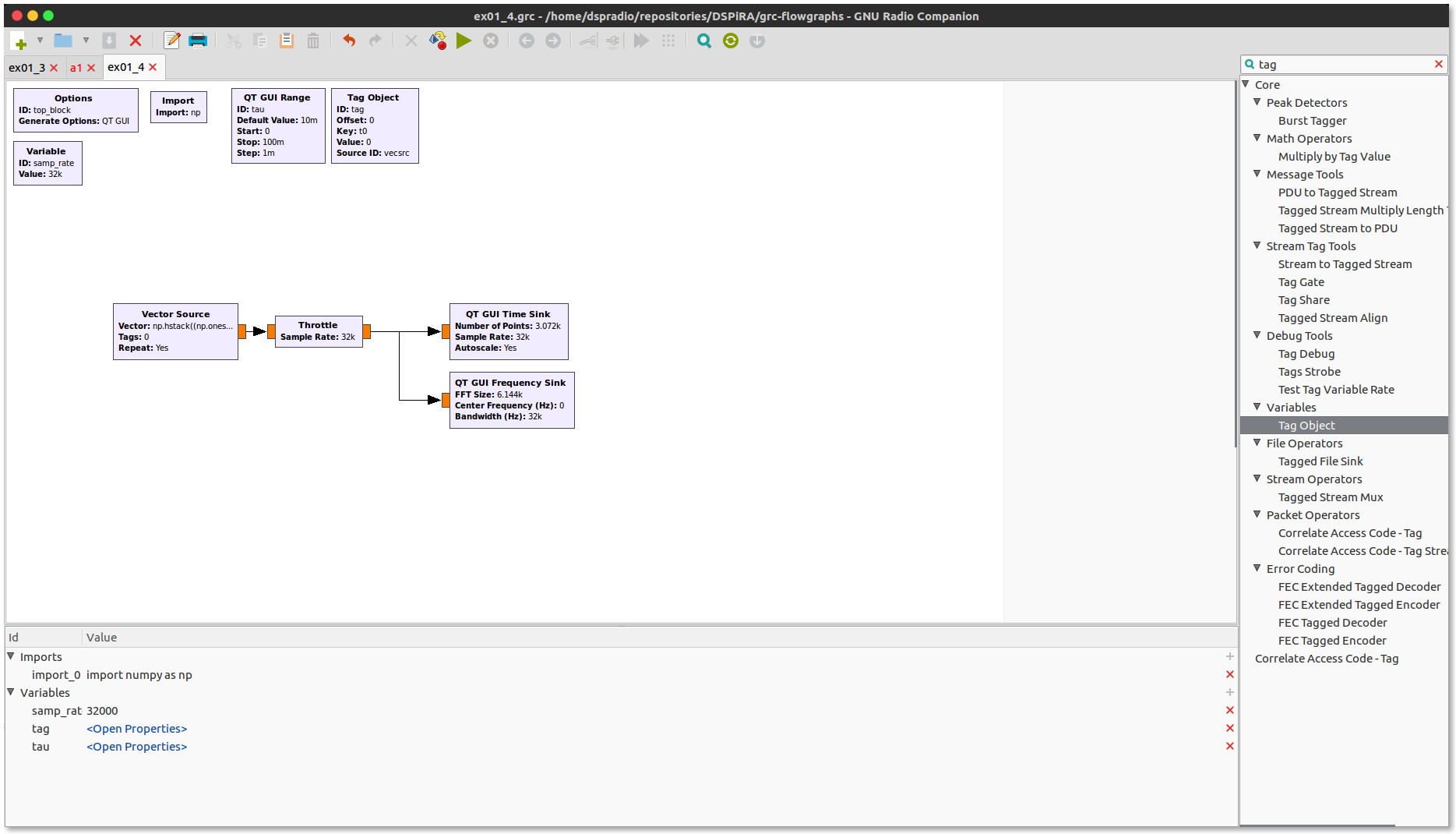

We shall make a rectangular pulse with variable width tau going from 0 to 10ms, we establish that range using the “QT GUI Range block”

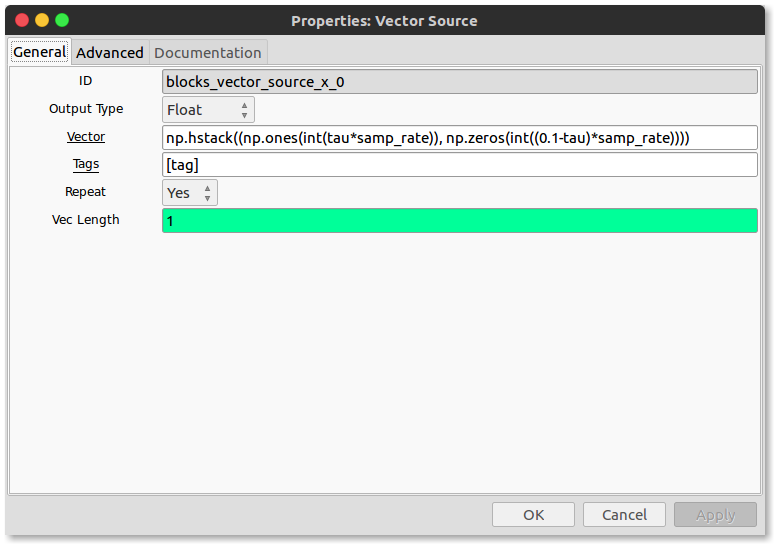

The function shall be generated shall be generated using the following python code:

np.hstack((np.ones(int(tau*samp_rate)), np.zeros(int((1-tau)*samp_rate))))

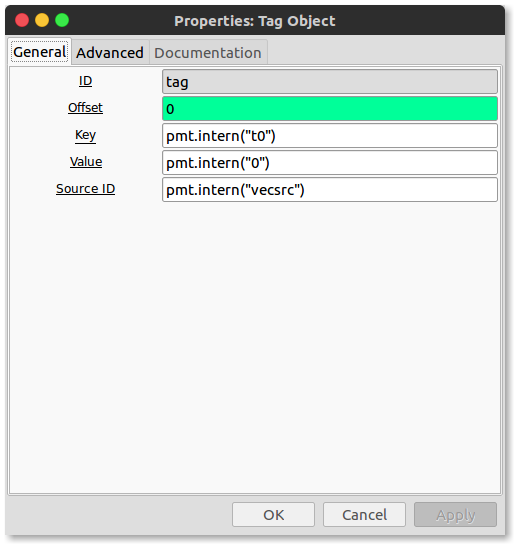

Before we place our blocks, we need to add consider a “Tag Object” block 1. It basically helps us synchronize the sinks when the generated stream tag associated with our vector source is stopped by the sink. This will alow us to observe the generated pulse. Vector Source has the “Repeat” field which is set to “Yes” so that the pulse of width tau is repeated periodically. Note the “Tag” field. The properties of the blocks are set as below:

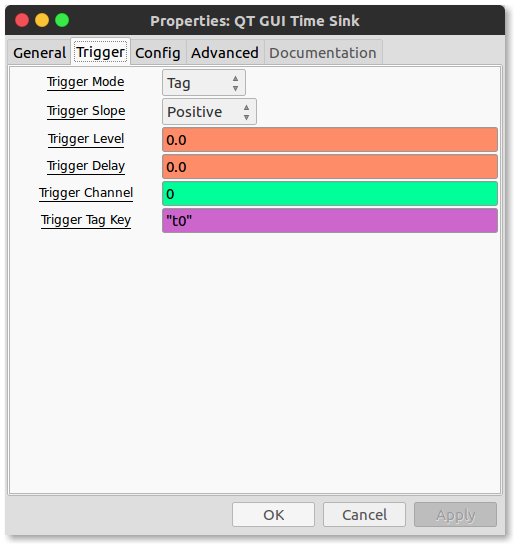

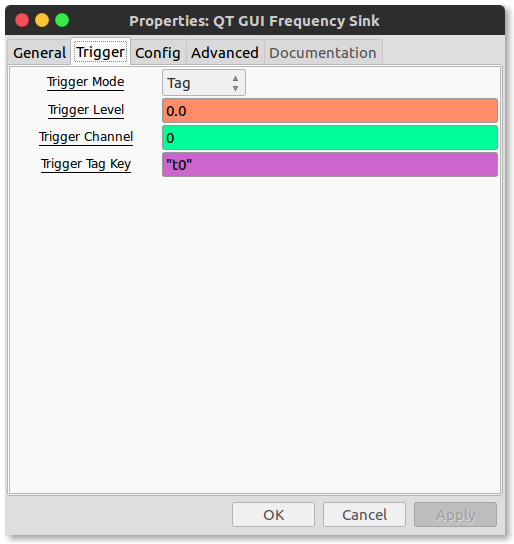

We set the sinks to have the trigger mode to “tag” and enter the “Tag Key” t0 and change the “Number of Points” in the time sink to “samp_rate” and in the frequency sink to “1024 * 6”. This is to properly visualize the signal and its frequency components.

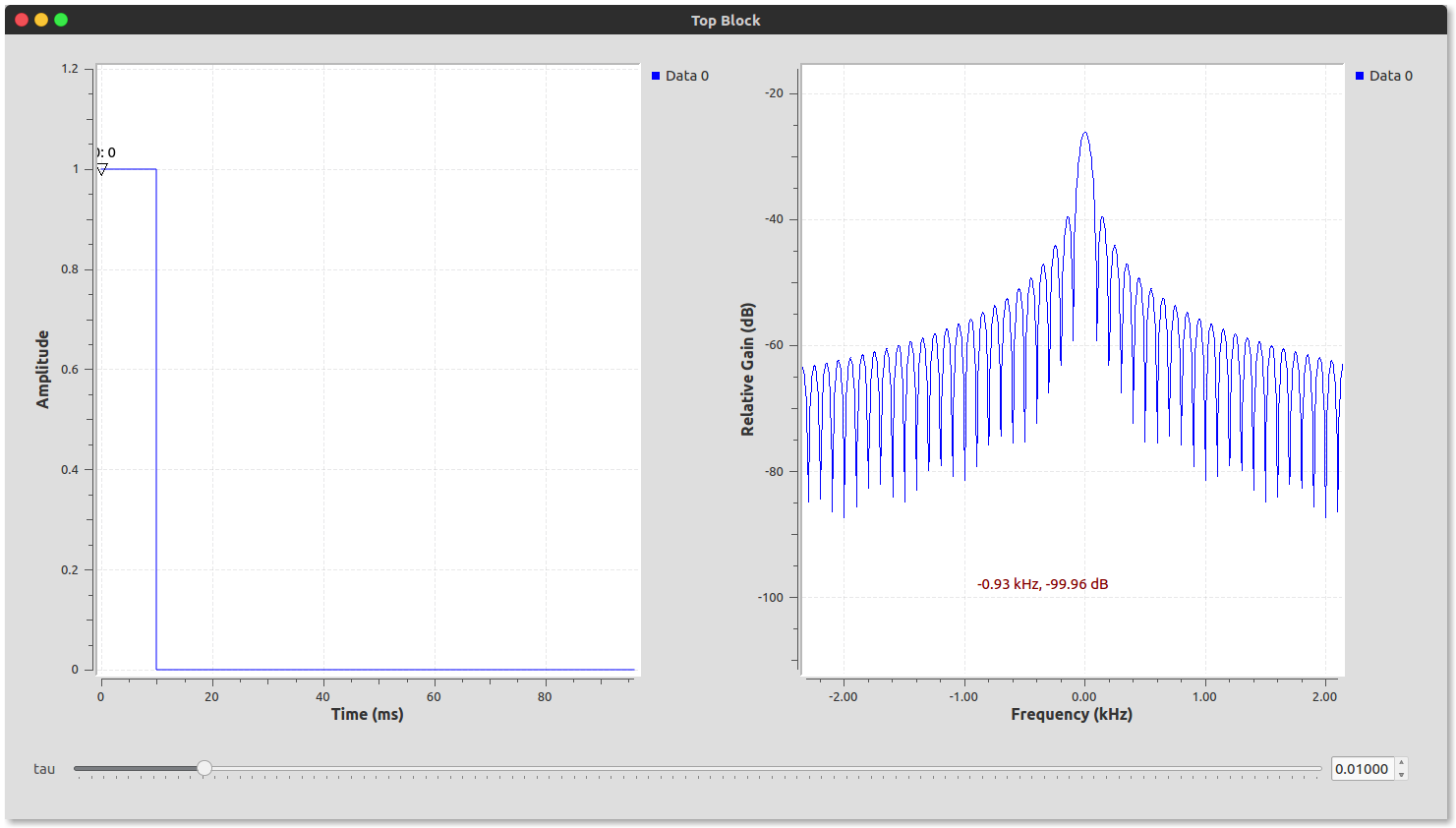

We should then have the flowgraph and output that looks like this:

1.5. Note on the Frequency Display

This particular display may not seem very intuitive for the those seeing it for the first time. It basically shows, as the name suggests, the ‘frequency’ components of the signal. This means the peaks in the graph represents the frequencies of the periodic signals that make up that particular signal. This is the basis of a very important concept called Fourier Analysis. Detailed discussions shall be done in class and systematically demonstrated in Lab 3 and Lab 5

1.6. Exercises

-

Delaying Signals: Use the “delay” block after the signal source and the value of delay can be controlled by a “GUI Range” to make a slider to have the delay change values from 0 to 2000. See how the the signal changes in a time sink. NOTE: The delay value indicates the delay in units of number of time samples. Each time sample is \(\frac{1}{\verb+samp_rate+} \rm{s}\)

-

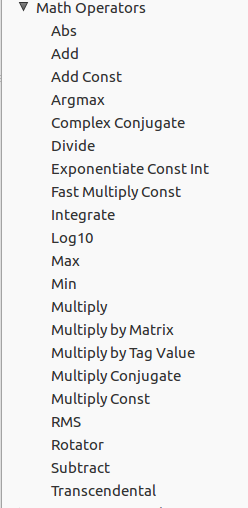

GNU Radio has a host of “Math Operators” that will allow you to perform a host of operations:

.

.

Use mulitple signal generators from section 1.2.3 to add and subtract and multiply to form new waveforms. We’ll add the examples here!

1.7. Random Discrete Signals

Random signals are signals where the next value can be though of as chips drawn from a hat with many many values, where the exact number of chips with those values relative to each other can be given by an equation, the ‘distribution’. One of the simplest is a uniform random signal, where each value has an equal number of chips.

In GnuRadio we can create these signals with a ‘Random Uniform Source’ block.

A very common distribution in nature is the ‘gaussian’ distribution.

1.8. Sampling

Sampling can always be though of as the act of pulling the chips out of the hat, and rounding the value on the chip to the nearest integer. When a real signal is digitized by an analog to digital converter (ADC), every clock cycle, the level of the signal is measured and recorded to the nearest value.

1.9. Histograms

A histogram is a plot of the number of occurrences of the signal that occur between a set of levels chosen. Plotting the histogram is a way of trying to measure the distribution of an incoming random signal.

1.10. GnuRadio Companion Example.

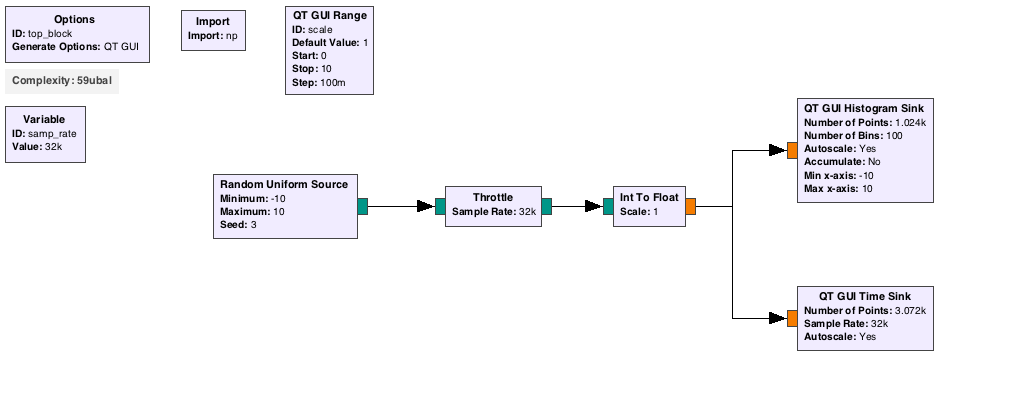

Create the shown GnuRadio flowgraph.

Use a random source between -10 and 10. The random source only creates discrete integer values, so you also need and Int to Float block with a ‘scale’ which will multiply the incoming signal by the scale value.

Run the flowgraph, with the scale factor at 1. What does the time plot look like? What does the histogram look like? Now play with the scale factor. Can the histogram have large gaps? Can you make the histogram look continuous? What intuition do you gain from this about sampling a ‘random’ signal?

Now also try different distribution sources. Use the “Noise Source” block and set it to a gaussian distribution. What does the time stream look like? What about the histogram?

Now again use a cosine input signal as you’ve used in a previous exercise. What does the time series look like? The histogram? A cosine signal is not very random. What if instead, each measured point in time of the cosine was completely randomized (could also think of using a uniform random signal put through a cosine function)? Would the histogram look any different? This would also be a random signal, and has the functional form \(\frac{A}{\sqrt{1-y^2}}\), which should agree with your histogram.

1.11. Make your own gaussian noise block

You are now ready to try to make your own gaussian noise block out of other blocks.

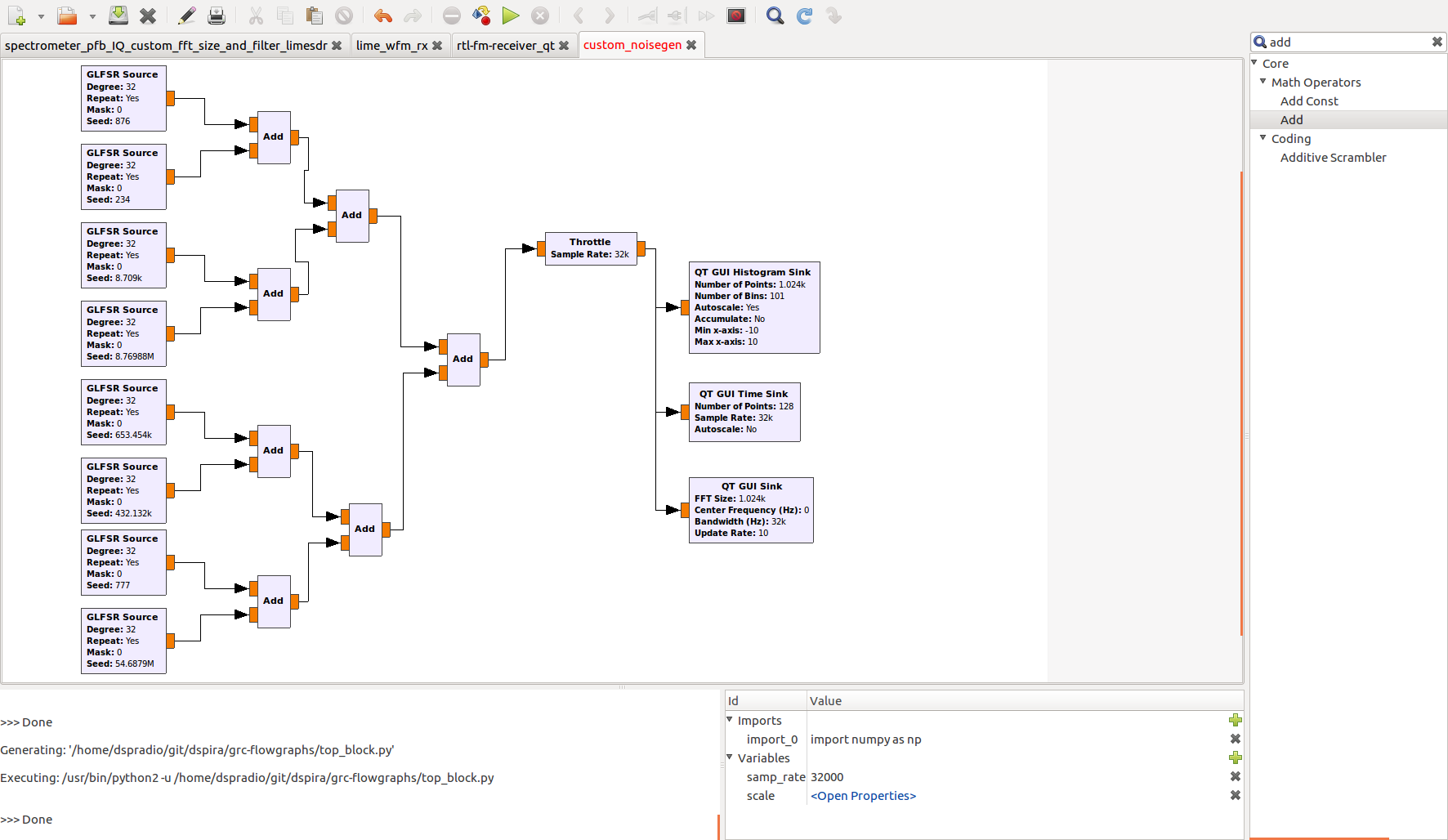

Create a new flowgraph in grc. We’ll start by using a just a QLFSR block. This is a ‘linear feedback shift register’ block, which is a very simple way to create ‘pseudorandom’ noise. Look here for more details. Set the type to float, the degree (how many elements in the shift register) to 32, repeat yes. Change the seed to any number. Leave the ‘mask’ at zero to get an ‘optimal’ source that wont repeat. Try using other numbers to compare, 1075838979 is a nice choice for random looking data. Use a histogram sink and a gui sink to look at the output. Even though the output is only -1 or 1, without knowing the initial seed and how many cycles have gone by, the answer is random.

Add a number of these sources together:

What does the output look like now? This is one of the simple ways of going from a ‘flat’ random number to a gaussian white noise.

↑ Go to the Top of the Page ……Next Lab

Extra Materials:

- A guided tutorial by gnuradio

- this tutorial has been adapted from this lab

-

For a technical explaination of the block click here ↩